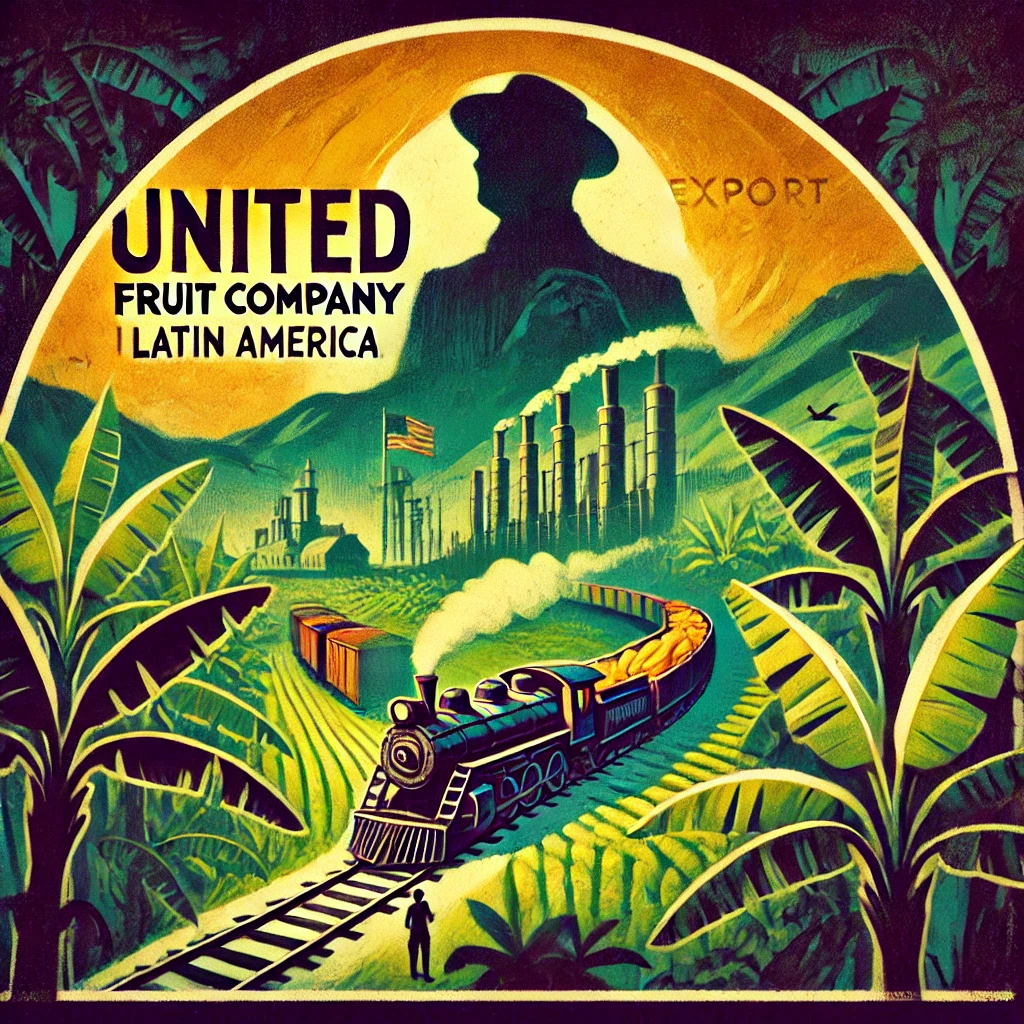

United Fruit Company: How a Corporate Giant Created the ‘Banana Republics’ of Latin America

Explore the story of the United Fruit Company and its profound influence over Latin America. From monopolizing the banana industry to orchestrating coups, discover how United Fruit became a ‘shadow sovereign,’ shaping the politics and economies of entire nations and creating the term ‘banana republic.’

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Founding United Fruit and Early Expansion

- United Fruit’s Economic Power and Monopoly

- Shaping “Banana Republics” Through Political Influence

- Using Propaganda to Gain U.S. Support

- The Overthrow of Guatemalan President Árbenz

- Labor Exploitation and Worker Resistance

- Decline of United Fruit’s Power in Latin America

- The “Banana Massacre” and Public Backlash

- Legacy of United Fruit and the Banana Republics

- Conclusion: United Fruit as a “Shadow Sovereign”

Introduction

In the early 20th century, the United Fruit Company (UFC) dominated the banana industry in Latin America, shaping entire nations’ economies, politics, and destinies. More than a fruit company, United Fruit was a powerful entity that influenced governments, ousted leaders, and carved out a unique empire fueled by bananas. By cultivating monopolistic control over production and export, United Fruit became a true “shadow sovereign,” a force behind the scenes that held sway over governments and economies. This is the story of how one corporation rose to rule through economic leverage, creating a legacy that would forever define the term “banana republic.”

Founding United Fruit and Early Expansion

The United Fruit Company was officially founded in 1899, though its origins stretched back a few years to a man named Minor C. Keith. Keith, a railroad entrepreneur from the United States, had undertaken an ambitious project in Costa Rica in the 1870s, constructing a railway that would connect San José, Costa Rica’s capital, with the Atlantic coast. Keith faced financial struggles throughout this project, and as a way to keep his railroad enterprise afloat, he began planting bananas along the railway. The crop was cheap to grow, easy to ship, and popular in the United States. By transporting bananas along his railway, Keith turned a struggling venture into a profitable one, laying the foundation for what would become United Fruit. In 1899, Keith merged his banana enterprise with the Boston Fruit Company, run by businessman Andrew W. Preston, and thus, United Fruit was born. From the start, United Fruit operated with a vision that went beyond mere commerce. The company bought land and planted bananas on a massive scale, establishing plantations across Central America and the Caribbean. They owned not only the banana fields but also the railways, ports, and shipping lines needed to transport the fruit back to the United States. This control over every stage of production and distribution allowed United Fruit to minimize costs, reduce reliance on external suppliers, and dominate the industry. With their reach spanning multiple countries, United Fruit’s influence began to grow. Their operations in countries like Honduras, Guatemala, and Costa Rica became so extensive that local economies depended on the company’s investments and exports. But United Fruit’s ambitions weren’t limited to agriculture. They used their economic power to shape local governments and policies, beginning a relationship with Latin America that would shape its political landscape for decades to come.

United Fruit’s Economic Power and Monopoly

By the early 1900s, United Fruit had positioned itself as a monopoly in the banana industry, a feat it achieved through an aggressive expansion strategy. The company acquired land at astonishing rates, buying out smaller plantations and consolidating power. Through these acquisitions, United Fruit created an empire of banana plantations that stretched across Latin America, giving them the power to control production, dictate prices, and eliminate competition. With such extensive holdings, United Fruit influenced Latin American countries’ economies, especially those heavily dependent on banana exports. In Honduras, for instance, banana exports represented over 60% of the country’s revenue, a figure that underscored how deeply the local economy relied on United Fruit’s operations. Honduras became one of several countries labeled “banana republics,” a term describing nations that were politically and economically controlled by foreign companies like United Fruit. To ensure stability and favorable policies, United Fruit established close relationships with local governments. In some cases, this meant providing financial support for friendly politicians; in others, it meant using its vast network and resources to sway public opinion. United Fruit’s involvement in these countries went beyond business, effectively integrating itself into the governance of nations. Company executives wielded influence like heads of state, meeting with Latin American leaders and even U.S. officials to negotiate policies that would protect their interests. The company’s monopoly extended beyond bananas to critical infrastructure. United Fruit owned entire transportation systems, including railroads, ports, and even telecommunications lines, which allowed them to control the flow of goods, people, and information. This extensive control gave the company a unique advantage: they could stifle competitors simply by limiting their access to transportation or distribution networks. This monopolistic approach turned United Fruit into more than just a company—it became an institution with far-reaching power over Latin America’s political and economic life.

Shaping “Banana Republics” Through Political Influence

As United Fruit’s power grew, so did its influence over local governments, a trend that defined the “banana republic” era. In the 1910s and 1920s, the company solidified its status as an unofficial “shadow sovereign” in several Latin American countries. The term “banana republic” originated as a description of nations like Honduras and Guatemala, whose economies were overwhelmingly dependent on banana exports and whose political leaders often catered to the interests of companies like United Fruit. One of the most striking examples of United Fruit’s influence occurred in Honduras. During this period, the company played a direct role in shaping the country’s political landscape. United Fruit used its financial resources to support candidates who aligned with their business interests, effectively buying loyalty from local leaders. These alliances ensured that Honduras, like other banana republics, would remain favorable to United Fruit, allowing the company to continue its operations without interference. United Fruit’s political influence didn’t stop at local governments. They also wielded power in Washington, D.C., lobbying U.S. officials to secure their interests in Latin America. Given the strategic importance of Latin America to the United States, the U.S. government was often willing to support United Fruit’s actions, viewing them as part of America’s broader sphere of influence in the region. In return, United Fruit presented itself as a stabilizing force, an American corporate presence that, in their view, benefited local economies. Through these relationships, United Fruit cemented its control over banana republics, effectively shaping policies that would benefit the company. The local governments in these nations often found themselves entangled in United Fruit’s network of influence. Policies that protected United Fruit’s monopoly became the norm, and any resistance to the company was swiftly met with financial or political retaliation. In this way, United Fruit achieved the power of a “shadow sovereign,” a corporate entity that controlled countries without holding formal political office.

Using Propaganda to Gain U.S. Support

By the 1930s, United Fruit was more than a business—it was a powerhouse of influence, using every tool available to maintain its monopoly in Latin America. With the term “banana republic” now widely recognized, United Fruit’s control over these nations became both a source of profit and a matter of international strategy. United Fruit executives understood that their power extended only as far as their support in the United States, so they focused on winning over the American public and government. United Fruit maintained a robust public relations machine, hiring journalists, diplomats, and lobbyists to shape their image in the United States. They portrayed themselves as benevolent corporate citizens, bringing infrastructure, jobs, and economic development to Latin America. Ads and promotional materials highlighted United Fruit’s contributions to the communities where they operated, showing photos of schools, clinics, and clean housing, painting the company as a force for progress. Behind the scenes, however, the company’s tactics were more complex. United Fruit wielded significant power over American media and even political leaders, often framing Latin America as a region in need of stability, which only they could provide. This narrative cast United Fruit as a stabilizing force and protector of American interests, making it harder for critics to question their influence over these “banana republics.” By maintaining the backing of U.S. officials, United Fruit ensured continued support for their dominance. American policymakers often saw the company as an ally in the fight against communist influence in Latin America, a concern that would only intensify in the years to come. This alignment with U.S. foreign policy gave United Fruit the freedom to operate without interference, effectively granting the company a license to shape political outcomes in the region.

The Overthrow of Guatemalan President Árbenz

One of the most significant episodes in United Fruit’s history—and arguably the pinnacle of its influence—was the 1954 overthrow of Guatemalan President Jacobo Árbenz. Árbenz had been elected in 1950 on a reformist platform, promising to address social and economic inequalities in Guatemala. His most controversial initiative was agrarian reform, a policy aimed at redistributing unused land to impoverished rural farmers. This reform directly threatened United Fruit, as the company owned vast tracts of land in Guatemala, much of which was left idle to keep banana prices stable. Under Árbenz’s plan, land that was not actively being used could be expropriated by the government and distributed to landless farmers. The plan offered compensation, but United Fruit considered it a direct threat to their operations and a dangerous precedent for other banana republics. The company launched a full-scale campaign to protect its interests, accusing Árbenz’s government of being sympathetic to communism. In the climate of the Cold War, this accusation was enough to gain attention in Washington, D.C., where the U.S. government was increasingly concerned about Soviet influence in Latin America. United Fruit hired Edward Bernays, a pioneering public relations expert, to sway public opinion against Árbenz. Bernays crafted a campaign portraying Guatemala as a communist stronghold, using media outlets to plant stories and shape American perceptions. The U.S. government, already wary of potential communist influence in its “backyard,” became increasingly receptive to United Fruit’s claims. In 1954, with support from the CIA, the U.S. government orchestrated a coup that removed Árbenz from power. The operation, known as **Operation PBSUCCESS**, was a turning point in both Guatemalan and American history. Árbenz was replaced with a government that was more sympathetic to United Fruit, and Guatemala returned to policies that favored the company’s interests. This intervention reinforced United Fruit’s image as a “shadow sovereign,” a corporation capable of influencing U.S. foreign policy to safeguard its own interests. For Guatemalans, however, the coup had devastating consequences. The country descended into political instability, leading to decades of conflict and repression. United Fruit’s role in the overthrow of Árbenz cast a dark shadow over its legacy, exposing the extent of its influence and the lengths to which it would go to protect its monopoly. The event also highlighted how corporate power could shape the destinies of nations, fueling resentment and resistance across Latin America.

Labor Exploitation and Worker Resistance

While United Fruit enjoyed immense power and influence, the company’s success came at a significant human cost. Workers on United Fruit plantations faced harsh conditions, low wages, and limited rights. The company’s dominance in the region left laborers with few options; most either worked for United Fruit or faced unemployment in areas where the economy was dependent on bananas. United Fruit’s grip on Latin American economies gave it leverage over labor, and they used this advantage to suppress worker demands. When labor movements emerged, United Fruit reacted swiftly to suppress them, often with the support of local governments. In countries like Honduras and Colombia, where United Fruit held considerable sway, strikes were met with strong resistance. In some cases, local authorities, under pressure from United Fruit, used force to break up protests, leading to violent confrontations. The company’s practice of hiring armed guards to maintain order on plantations underscored its willingness to exert control by any means necessary. One of the most infamous incidents occurred in 1928 in Colombia, long before the events in Guatemala but emblematic of United Fruit’s labor policies. Known as the **Banana Massacre**, Colombian workers organized a strike demanding better working conditions, fair wages, and recognition of their union. United Fruit, concerned that the strike could set a precedent across its plantations, pressured the Colombian government to intervene. In response, Colombian soldiers opened fire on the striking workers, killing an unknown number—reports range from dozens to hundreds. This brutal episode served as a chilling example of United Fruit’s influence and willingness to leverage government power to maintain control. The “Banana Massacre” left a lasting scar on Colombia’s history and became a symbol of resistance against foreign corporate power in Latin America. The incident also revealed the stark contrast between United Fruit’s image as a progressive force in its promotional campaigns and the reality faced by workers on the ground. The exploitative labor practices and suppression of workers’ rights gradually fueled resentment against United Fruit, sparking calls for reform across Latin America. Activists and leaders began to question the company’s unchecked influence, laying the groundwork for future movements aimed at reclaiming sovereignty from foreign corporations. Yet despite these challenges, United Fruit continued to hold significant power in the region, a testament to its deep-rooted influence and the dependency of banana republics on its investments.

Decline of United Fruit’s Power in Latin America

By the 1960s, United Fruit’s iron grip over Latin America began to loosen. A wave of social and political changes swept across the region as movements for labor rights, land reform, and national sovereignty gained traction. These shifts posed significant challenges to United Fruit, as more Latin American leaders sought to limit foreign control over their economies and reinvest in local development. The Cuban Revolution in 1959 had already fueled anti-imperialist sentiment across the continent, inspiring resistance against corporations like United Fruit. In Honduras, Guatemala, and other banana republics, workers continued to demand better wages and conditions. Labor unions became stronger, organizing strikes and protests that received increasing support from Latin American governments. Although United Fruit attempted to quell these movements, the company was no longer operating in a political climate that could be as easily manipulated. Local governments began asserting their authority, and calls for economic independence grew louder. One major blow to United Fruit came in 1958 when Eli Black, an American businessman, took control of the company. Under Black’s leadership, United Fruit was rebranded as the **United Brands Company** in 1970, a move intended to modernize its image. Despite efforts to revitalize operations, the company continued to face political and financial struggles. Rising labor costs, new competition, and the increasing scrutiny of its practices placed financial strain on United Fruit. By the early 1970s, United Brands was far from its former dominance, struggling to maintain profitability and relevance in a changing world.

The “Banana Massacre” and Public Backlash

As United Fruit’s influence declined, the darker aspects of its history began coming to light. Reports of the 1928 **Banana Massacre** in Colombia resurfaced, drawing public attention to the human rights abuses and violent labor practices that the company had used to maintain control. The massacre, once buried under decades of corporate influence, was now recognized as a tragic symbol of exploitation and oppression. The resurfacing of this incident fueled a broader public backlash against United Fruit. Activists, journalists, and Latin American leaders criticized the company’s history of exploitation, and public opinion in the United States began to shift. Where United Fruit had once been seen as a benign or even beneficial presence, it was now regarded by many as a symbol of imperialism and corporate greed. The backlash intensified in the 1970s as a new generation of activists demanded accountability for United Fruit’s past actions. The company’s history of influencing foreign policy, exploiting workers, and wielding power over Latin American governments became topics of widespread discussion. Although United Fruit had rebranded as United Brands, the public perception of the company had been irreversibly damaged. The “banana republic” label, once a mere description, had become a cautionary tale of corporate overreach and foreign intervention.

Legacy of United Fruit and the Banana Republics

By the 1980s, United Fruit was a shadow of its former self. It no longer held the monopoly it once enjoyed, and its influence over Latin American politics had waned. Yet the legacy of United Fruit’s actions lived on. The term “banana republic” had entered the lexicon, symbolizing a country whose government and economy are dominated by foreign corporate interests. For many in Latin America, United Fruit’s history represented a painful reminder of the exploitation and dependency that had stifled their nations’ development. Despite its decline, the legacy of United Fruit had lasting effects on Latin American politics and economies. The company’s role in creating banana republics inspired resistance movements and fueled anti-imperialist sentiment across the continent. Leaders like Guatemala’s Árbenz became symbols of national sovereignty, and the struggle for economic independence became a recurring theme in Latin American history. The company’s actions also highlighted the dangers of corporate power in vulnerable economies, contributing to discussions about sovereignty and self-determination that would shape Latin America’s political landscape for years to come. Furthermore, United Fruit’s history of labor abuses brought attention to the need for workers’ rights and fair labor practices. The company’s suppression of unions and violent responses to strikes became emblematic of the broader exploitation faced by Latin American workers. The rise of labor movements and pro-worker policies in the region owed much to the hard lessons learned from United Fruit’s history. Today, United Fruit’s legacy lives on through its successor, **Chiquita Brands International**. Although it has rebranded multiple times and changed leadership, the company’s complex history in Latin America remains a source of scrutiny and debate. For many, Chiquita carries the weight of United Fruit’s actions, a reminder of the power that corporations can wield and the impact they can have on the lives and destinies of entire nations.

Conclusion: United Fruit as a “Shadow Sovereign”

The story of the United Fruit Company serves as a powerful example of a corporation that acted as a “shadow sovereign.” Through economic control, political influence, and aggressive labor practices, United Fruit held sway over Latin America’s “banana republics” for decades, shaping policies and overthrowing leaders in pursuit of profit. The company’s influence extended beyond commerce; it altered political landscapes and left a lasting impact on Latin American society. United Fruit’s legacy is a reminder of the potential dangers of unchecked corporate power. As one of history’s most notorious “corporate shoguns,” United Fruit wielded its influence without accountability, operating as a de facto government over the banana republics. The rise and fall of United Fruit underscored the importance of sovereignty and the need for nations to protect themselves from foreign dominance, a lesson that continues to resonate today. Though United Fruit no longer exists as it once did, the lessons from its history are clear. Economic power can be as potent as political power, and corporations—when allowed to operate without oversight—can shape the fates of nations. The story of United Fruit and the banana republics stands as a testament to the influence of corporate entities and the responsibility of governments to guard against their overreach. In the history of “shadow sovereigns,” United Fruit remains a powerful symbol of corporate dominance, one that serves as a cautionary tale for generations to come.

References

-

Bananas: How the United Fruit Company Shaped the World by Peter Chapman

A comprehensive history of United Fruit’s influence over the banana industry and Latin America. Canongate U.S.

-

Bananas and Business: The United Fruit Company in Colombia, 1899–2000 by Marcelo Bucheli

A thorough look into United Fruit’s operations in Colombia, covering its political influence.” NYU Press

-

Bitter Fruit: The Story of the American Coup in Guatemala by Stephen Schlesinger and Stephen Kinzer

Details United Fruit’s involvement in the 1954 Guatemalan coup and its impact on U.S. foreign policy. Harvard University David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies

-

The Fish That Ate the Whale: The Life and Times of America’s Banana King by Rich Cohen

An account of Samuel Zemurray’s role in United Fruit’s rise and influence in Central America. Picador

-

Empire’s Workshop: Latin America, the United States, and the Rise of the New Imperialism by Greg Grandin

Explores the U.S. influence in Latin America, with insight into United Fruit's political impact. Holt Paperbacks