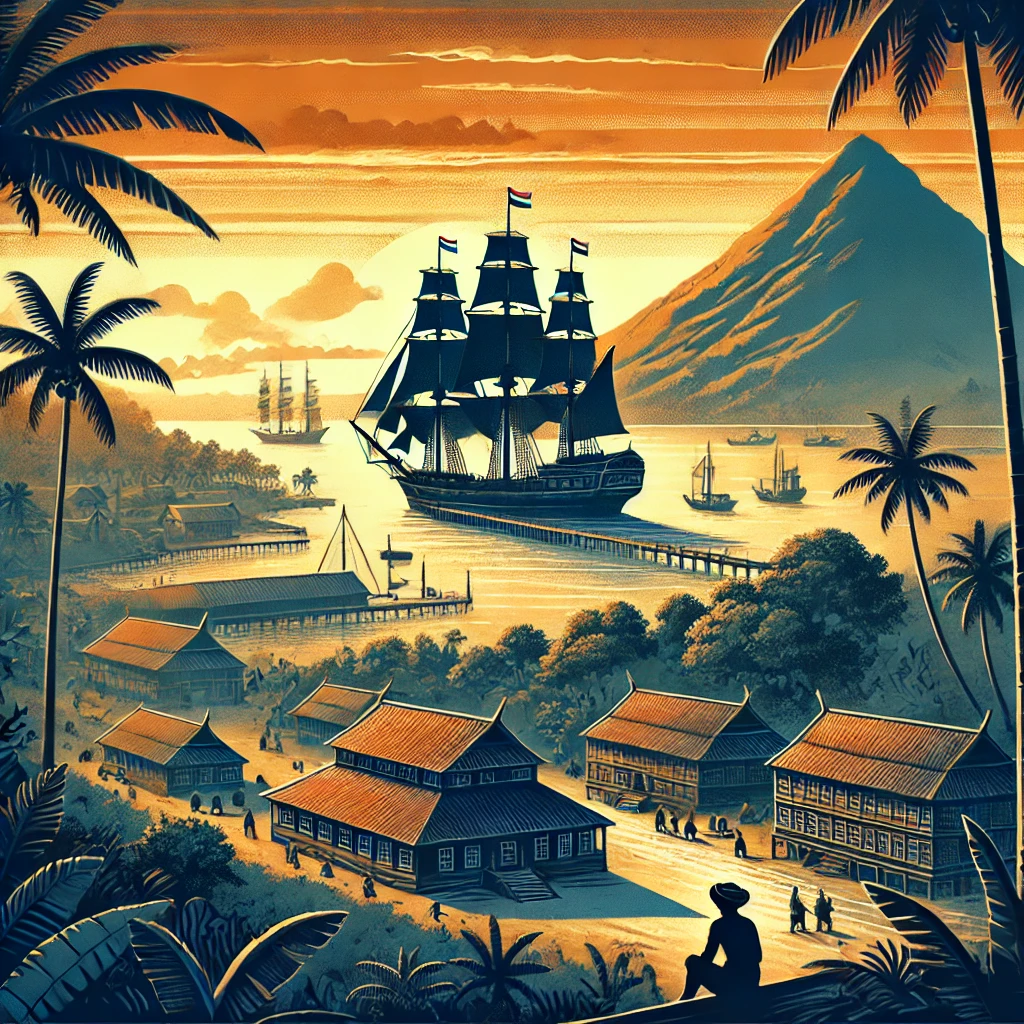

Part 2: Expansion into Asia – Conquest and Control

Uncover the Dutch East India Company’s expansion across Southeast Asia, as it established monopolies, controlled lucrative spice trade routes, and exerted influence over local rulers. This part dives into the VOC’s role in shaping Asia’s colonial history and its impact on local economies.

Table of Contents

Enforcing a Corporate Empire

As the VOC solidified its control over the spice trade, its operations transformed from mere trade deals into a powerful web of influence and exploitation. The company wasn’t just interested in trading spices—it wanted to control their production, distribution, and sale, securing every link in the chain. This meant enforcing its rule over the Indonesian islands with a force that could rival any European army. With its headquarters in Batavia, the VOC expanded its network of forts, garrisons, and trading posts across Southeast Asia, each one a node in a carefully managed system of control. These outposts weren’t just business centers; they were military fortresses, designed to secure VOC assets and intimidate anyone who dared challenge its authority. The locals quickly learned that the VOC’s presence wasn’t just about buying and selling. It was about domination. The VOC imposed harsh policies on the people of the Spice Islands, particularly in Banda. To maintain control over the valuable nutmeg trade, the company restricted who could plant, harvest, and sell the spice. Anyone who attempted to trade with rival companies—especially the English or Portuguese—was met with swift punishment. Villages were razed, rebels were executed, and local leaders were coerced into signing exclusive contracts with the VOC. By the 1620s, the Banda Islands had effectively become a VOC-run colony, their inhabitants subject to the company’s iron-fisted rule.

The Makassar Conflict: Crushing Competition

One of the greatest threats to the VOC’s monopoly came not from a European rival but from a Southeast Asian port city—Makassar. Located on the island of Sulawesi, Makassar was a thriving trade hub where merchants from across Asia gathered to exchange goods, including the precious spices the VOC sought to control. Makassar’s rulers had welcomed traders from all nations, believing that open commerce benefited their city’s economy and culture. This philosophy was, of course, a direct threat to the VOC’s monopoly. In the 1660s, the VOC decided to take action. Led by Governor-General Cornelis Speelman, the VOC launched a campaign against Makassar to end its open trade policy and secure VOC dominance. Speelman’s forces, equipped with advanced Dutch artillery and seasoned troops, besieged the city in 1667, forcing Makassar’s rulers to surrender. The Treaty of Bungaya was signed, effectively ending Makassar’s independent trading rights and binding them to VOC-controlled commerce. The fall of Makassar was a major victory for the VOC. By eliminating Makassar as a free trade port, the company tightened its grip on the spice trade, ensuring that all spices bound for European markets passed through VOC hands. The conquest also sent a clear message to other Southeast Asian rulers: resist the VOC’s monopoly, and you could face the same fate.

The Power and Perils of Monopoly

With Makassar subdued and the Banda Islands firmly under control, the VOC’s monopoly was nearly unbreakable. But this level of dominance came at a cost. Securing and defending these territories required a vast network of soldiers, ships, and administrators, all of whom expected to be paid. Maintaining the infrastructure of forts, warehouses, and supply chains stretched the VOC’s resources thin. To cover these expenses, the VOC levied taxes on the local populations it ruled, extracting resources and labor whenever necessary. In places like Java, the company imposed a “forced cultivation” system, compelling farmers to grow cash crops like coffee, sugar, and indigo, which the VOC could sell at a profit. This system increased the company’s revenues but had devastating effects on the local economy and people, who were often left with little to support themselves. The VOC’s heavy-handed approach fostered resentment among the indigenous populations, who saw the Dutch as foreign oppressors. Rebellions occasionally flared up, forcing the company to divert resources into putting down uprisings. Each rebellion was a reminder that while the VOC could wield power through force, it was constantly at risk of losing its control. To manage these risks, the VOC’s governors in Batavia developed a complex network of alliances with local rulers, using a combination of bribes, promises, and threats to keep potential adversaries in check.

Governance and Corruption: The Company as a State

In many ways, the VOC functioned as a state within a state. The company’s directors, known as the Heeren XVII (Lords Seventeen), made decisions that affected not only trade but also diplomacy, law, and governance. They appointed governors, set taxes, regulated trade, and even conducted negotiations with Asian empires as if they were a sovereign power. This level of autonomy, though a source of pride for the Dutch, introduced a new set of problems. Without strict oversight from the Dutch government, VOC officials had enormous freedom to pursue personal wealth. Many governors and administrators exploited their positions, engaging in corrupt practices like embezzling funds, overcharging local leaders for services, and accepting bribes. Corruption became so rampant that it often affected the company’s efficiency, as bribes and personal profits took precedence over official duties. For local populations, VOC rule became synonymous with extortion. Rather than fostering stability and prosperity, VOC governance often destabilized regions, leading to cycles of resistance and repression. The company’s leaders saw these struggles as the price of doing business, but the people of Southeast Asia bore the brunt of the VOC’s drive for profit.

Battling Rivals and Securing Trade Routes

Despite its dominance, the VOC still faced competition from other European powers, especially the English East India Company (EIC). The two companies clashed frequently over trade rights, particularly in the Indian Ocean and Southeast Asia. The VOC’s fleet was superior, but the EIC was persistent, and skirmishes between the two were common. In 1619, tensions boiled over when the VOC captured an English trading post in Jakarta, further souring relations. The rivalry wasn’t just about spices. Both companies wanted control of the broader Asian trade network, which included textiles, tea, porcelain, and opium. To secure its position, the VOC established a series of fortified trading posts along critical routes, from Ceylon (Sri Lanka) to the Cape of Good Hope. These outposts allowed the VOC to control the flow of goods and protect its ships from pirates and rival companies. By the mid-17th century, the VOC’s presence spanned from the Indian Ocean to the Far East, creating a network of ports that safeguarded its trade empire. These fortified posts weren’t just for defense; they were economic hubs that linked European markets with Asian suppliers. The VOC’s ability to maintain these connections gave it an unparalleled advantage in global trade. However, as the company expanded, so did its logistical challenges. With outposts scattered across continents, the VOC found it increasingly difficult to manage its far-reaching empire, and cracks began to appear in the company’s once-ironclad structure.

The Toll on the Netherlands and Indigenous Populations

While the VOC’s dominance enriched many in the Netherlands, especially in cities like Amsterdam, it also created economic disparities. The wealth generated by the VOC funded grand architectural projects, supported the arts, and elevated the Netherlands’ status as a global power. But for ordinary Dutch citizens, the VOC’s riches often seemed out of reach. Only the elite, including wealthy merchants and investors, reaped the benefits of the company’s vast empire. Meanwhile, the indigenous populations across the VOC’s territories suffered under its rule. Forced labor, oppressive taxes, and restricted trade devastated local economies. The people who cultivated spices and other cash crops saw little of the wealth they generated, as VOC officials kept profits flowing back to Europe. For many in Southeast Asia, the VOC was not a partner in trade but a foreign oppressor, one that drained resources and imposed foreign customs on their lives. The VOC’s impact on indigenous cultures was profound. Traditional systems of governance were often dismantled, local leaders were replaced or co-opted, and European customs were introduced. This created cultural shifts that would have lasting effects on Southeast Asia, as European ideas about commerce, governance, and religion influenced the local way of life. The VOC’s legacy was not merely one of wealth but also of cultural transformation—a blend of forced assimilation and resistance that shaped the region’s future. In the final part, we’ll explore the VOC’s eventual decline, the internal and external factors that led to its downfall, and the legacy it left behind as the world’s first corporate empire. The VOC’s rise and fall serve as a testament to the power of ambition and the consequences of unchecked corporate rule.

References

-

The Dutch Overseas Empire, 1600–1800 by Pieter C. Emmer

A detailed examination of Dutch imperialism and VOC practices. Cambridge University Press

-

Empires of the Sea: The Final Battle for the Mediterranean by Roger Crowley

Covers European conflicts over trade and dominance in maritime Asia. Faber & Faber